Moving the Ball

Lessons from a gridiron past

“...125 Fake to 133 Crossbuck; 125 FAKE, to 133 CROSSBUCK, on three, on 3...”

That directive was spoken in a deliberate, almost solemn tone by a seventeen-year-old quarterback of a small private school football team, on a cold late November Friday afternoon as the sun was beginning to set, when I was fifteen. I shall never forget those instructions. Today, more than sixty years later, I recall with great fondness and gratitude how the ensuing seconds, minutes, hours, and years following and influenced by that activity have demonstrated the good received and dominion gained.

The play was designed to enable my team to overcome a three-point deficit and win the game in its closing seconds against a strong rival, Halstead Academy. As we mustered for the play, an adrenaline rush, which I had experienced previously, but never one accompanied by such resolve, was tinged by trepidation. Hurrying into position, I quickly processed my role: at the snap of the ball from center to quarterback (the one-back), I was to feign a few steps to my right as if I would be blocking for the older, bigger, running back (two-back) on my left; he would simultaneously cross in front of me, in an attempt to deceive Halstead’s defense that he, a senior and one of the stronger players in our league, would be the ball carrier on the play. Instead, using misdirection, I (the three-back) would receive the ball from the quarterback, who would then look to block any opposing defensive player who might penetrate our offensive line. Ball secured firmly, I was then to seek an opening in the three-hole, the space to be made between the left end and interior linesman, and cross the goal line before the game ended.

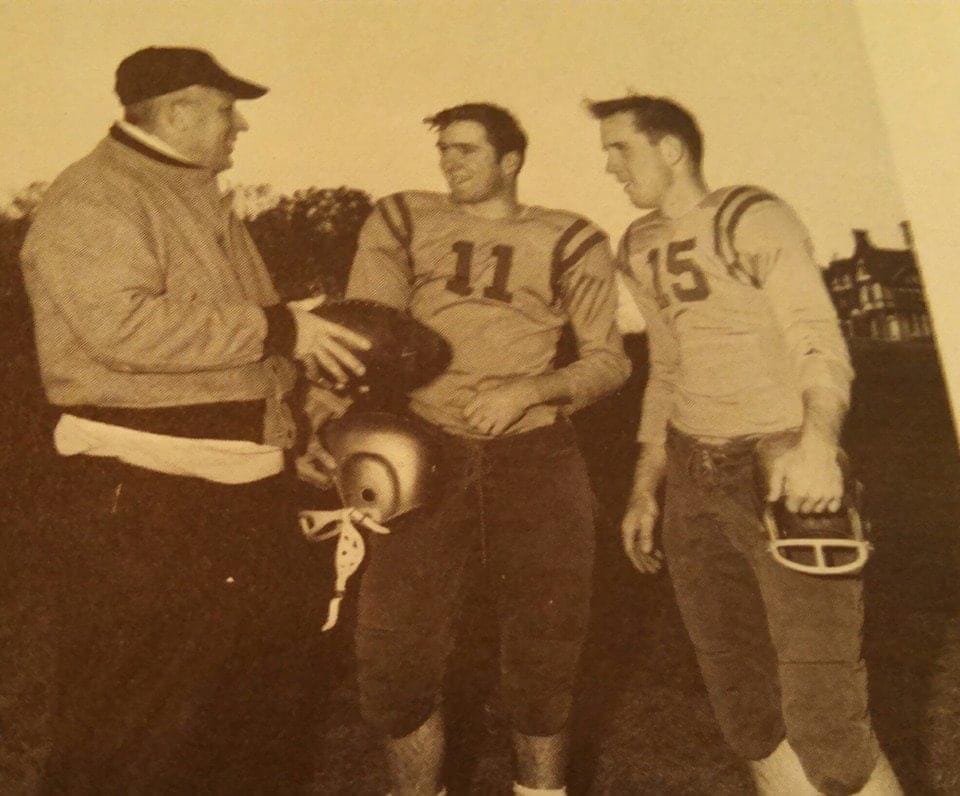

It all happened so fast, and yet the memory plays out in slow-motion. Hitting the line with legs pushing hard, I heard the oddly comforting symphony of tested masculinity, strong young warriors colliding furiously in oppositional intent, accompanied by a chorale crescendo of fiercely visceral, adolescent perturbation, a referee’s piercing final whistle accentuating the cacophony, as it signaled the end of the game. I lay at the bottom of a pile, clutching the pigskin and hearing the whistle, grunts and growls ebbing, vulgar pronouncements muttered in resignation. As I peered out from the pile of limbs and torsos atop me, I was informed by my coach’s jumping up and down, arms flailing in wild celebration as he approached the pile to help extricate players from it. As he helped me up, he declared my name loudly, with hugs and words of praise and elation punctuating the win. The sportsmanship demonstrated by both teams as we subsequently lined up to respectfully congratulate each other on a great game played by two good teams on a cold November day was palpable—never to be forgotten.

I was on cloud nine for the next few days, savoring the sports-page reportage in the local paper, sheepishly accepting compliments from neighborhood adults and friends, and indulging boyish dreams of professional sports in my future. It was also the first time the intoxication of pride to which the human ego is vulnerable invited fanciful dreams of the future. Those dreams came to a painful end a few years later, when I sustained a painful knee injury at a time when the risks attending surgical remedies lacked the favorable outcome rewards postured today.

These memories speak to lessons which many never learn, and argue for youth sports generally, and American football in particular: about risk, informed choices, self-awareness; about the value of camaraderie, the homely connection between sacrifice, toil, and shared success; and the overcoming of fear, doubt, resentment, pride, and many other impediments which have appeared to humans from time immemorial. The lessons learned while moving the ball down the field on cold autumn days can be salutary.

Support Us

Support Us

Comments ()