WWII in Memoriam, England

Subtle reminders of a senseless time.

In 2006, I took a trip to England. I was based in London and made several day-trips out. I decided I needed to visit all 46 of the Christopher Wren London City Churches (or what remains of them). What I stumbled upon was a treasure, a kind of scavenger hunt, if you will. When England was rebuilding the churches after the war, the restorers took it upon themselves to include a memorial to the war in the form of stained-glass windows. What follows is a brief look at two restorations, and a free-standing memorial outside of London.

(Most of the photographs are from my private collection, forgive the miscellaneous people milling about.)

St. Lawrence Jewry

St. Lawrence Jewry (rebuilt by Wren 1670-1687, subsequently restored in 1957 by Cecil Brown after Christopher Wren’s original design).

The building sits in a very strange position. It appears as though someone dropped it like a block in the middle of the guild courtyard. It was discovered as late as 1988 that the building’s foundation (and the guildhall’s) sits atop the remains of a Roman amphitheatre. For a Wren building, it certainly does not look like a Wren building, but more like a Grecian temple with an off-tenor bell tower.

The building’s interior was burned out in December, 1940. Much of the structure survived The Blitz, but nothing of the interior. The spire of the bell tower was burned out completely. It was rebuilt to align with the courtyard, not the building.

One thing I noted on that trip to England was a practice of placing a memorial to the war hidden in the stained glass of the buildings that had to be rebuilt, or restored. The stained glass windows of St. Lawrence Jewry appear at regular intervals along the walls. (This is a restoration decision that was contrary to the Wren design. Most of Wren’s designs feature clear leaded glass windows—to bring the light in.) They are mainly clear-paned, but there are various persons and emblems represented in the stained glass (Christopher Wren is depicted in one of them).

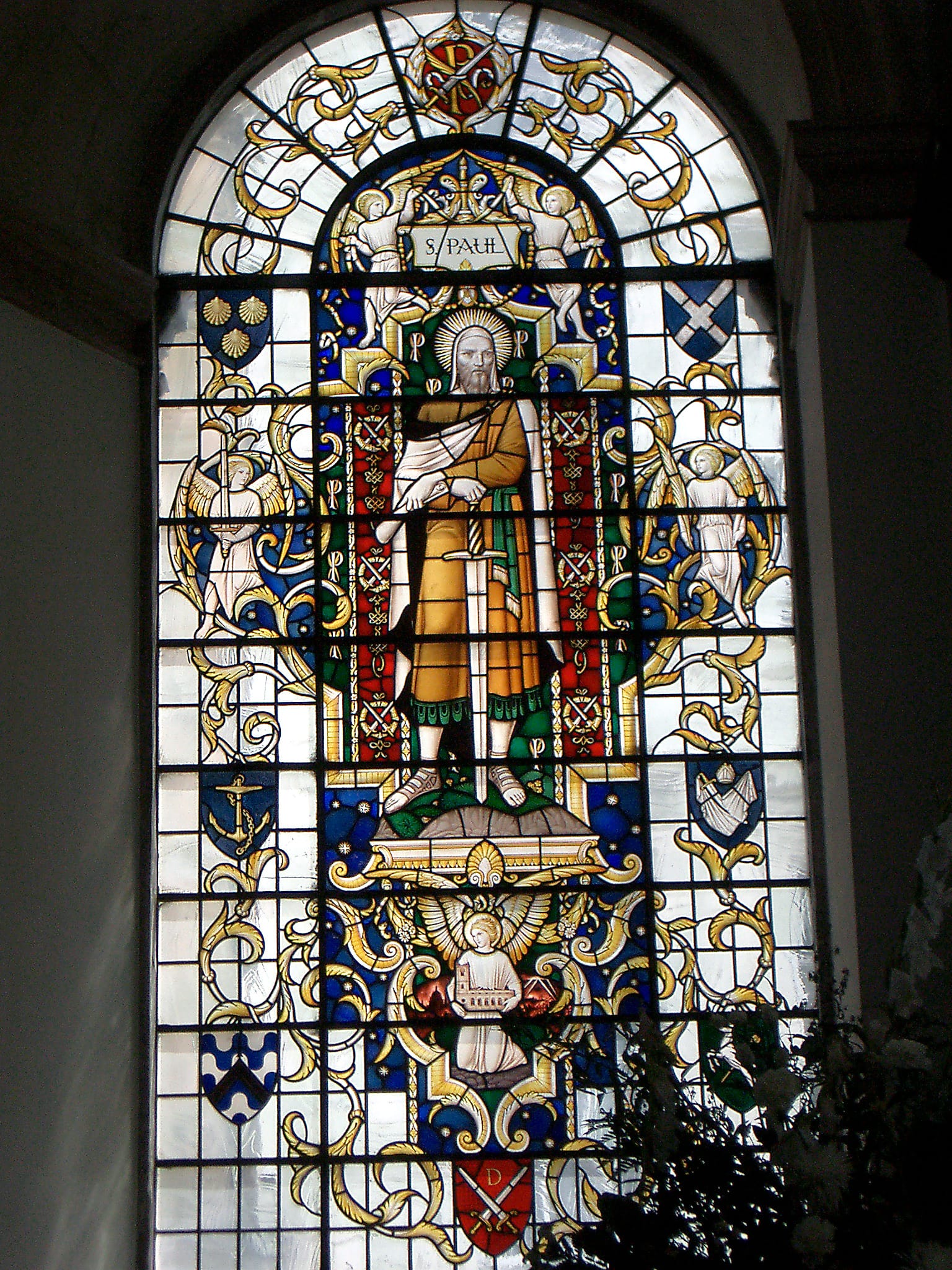

Because of the position and number of the windows, I had a bit of trouble finding the “war window.” At the chancel-end of the room, there are two windows flanking the altar, St. Paul to the left, St. Catherine to the right. At the bottom centre of each of these windows is an angel “holding” the building. In the St. Paul window, one can see the building in ruins.

In the St. Catherine window, the building is fully restored. If one looks very carefully at the St. Paul window, one can see that not only is the building in ruins, but in the distance on the left, St. Paul’s cathedral is backlit in red representing flames, on the right, the sky is the same red with buildings aflame, and there are streaks of search lights. Subtle, but moving all the same.

One has to be less than a foot from the window to see this detail. Given its position to the left of the altar, one would be hard-pressed to see it as most people do not approach the altar area (obviously, I do not have that issue).

Temple Church

The Temple Church gained an increased notoriety after a certain novel by Dan Brown was published and subsequently made into a feature film. This is unfortunate. When I was there, I approached the lovely English woman who was attending to the gifts table. She heard my accent and immediately concluded that I was there because of the book. I quickly assured her of my reason for being there and asked if she had any recordings of the organ and/or choir (it is an acoustically perfect room for singing). She gave me a little smile and expressed her distaste for all of the “adventure” seekers trying to recreate the novel. She even gave me a CD free of charge. (I put money in the coffers for the upkeep of the church regardless. She gave me another little smile and wished me good day.)

The Temple Church was built and consecrated by the Knights Templar in 1185. The building is not a traditional shape; it is in two parts: the Round Church and the Chancel (which is more like a nave in traditional church architecture vernacular). The Round Church was modelled after the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The building was nearly destroyed in 1941. This building, too, had a history with Christopher Wren. Somehow Wren’s drawings were saved from the fire and were used by Walter Godfrey in the renovation. The building was re-dedicated in 1958.

Because the Temple was a very important building to the royals and various other groups, there are photographs of the interior that survive predating its 1941 fire-bombing. As with St. Lawrence Jewry, all of the window glasses were melted from the intense heat. These were re-crafted as closely as they could to the originals. Wren’s designs for the Temple Church were a departure from his other designs because of the importance and history of the building. Consequently, the windows were stained glass, not clear.

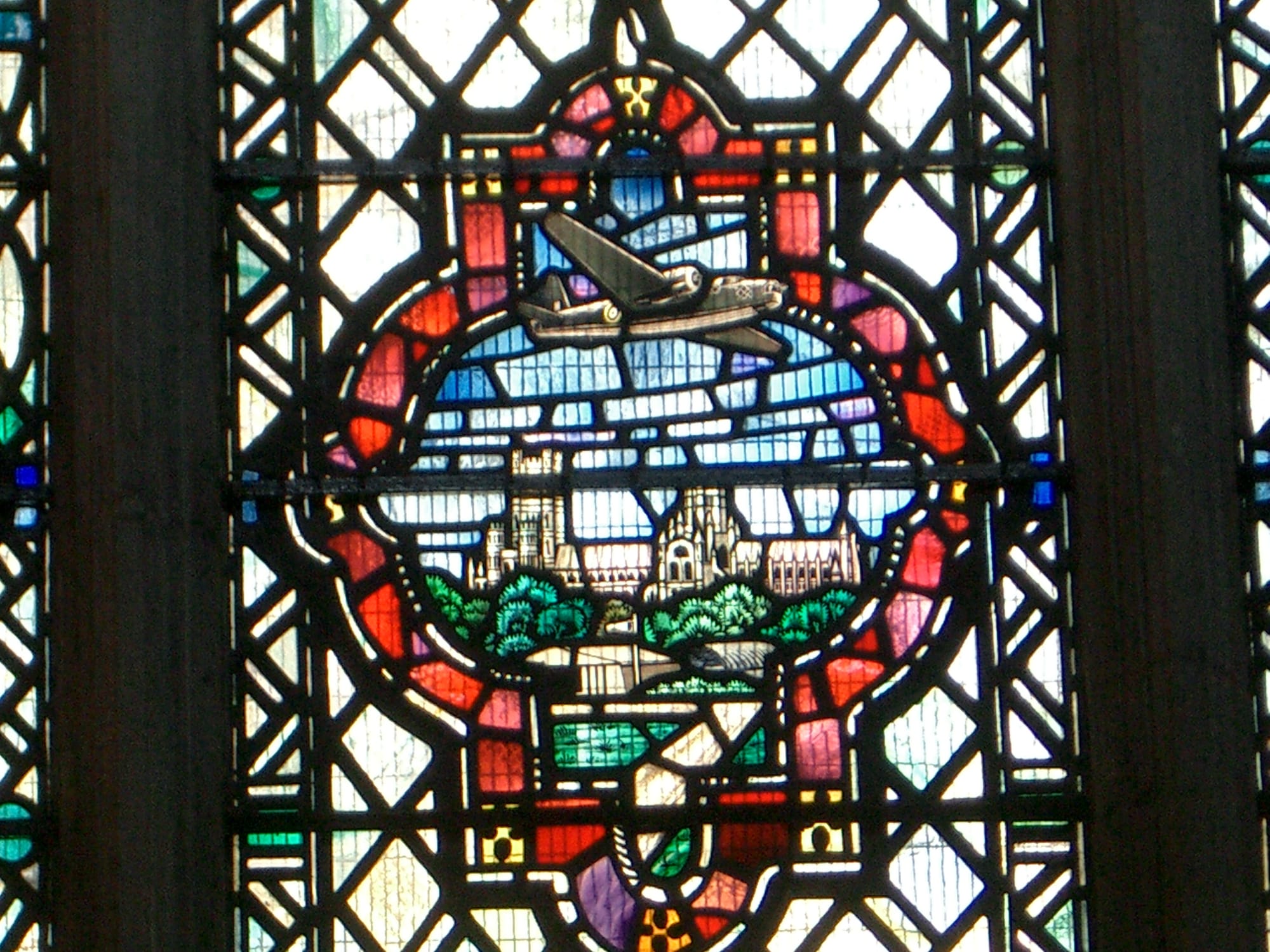

There are many windows in the Temple Church, just like St. Lawrence Jewry. After a similar design fashion, the “war window” is located directly over the altar. The window contains hundreds of pieces of glass.

Unless you know what it is you are looking for, the war memorial is not readily apparent. Once you know it is there (middle-left), you cannot, as the saying goes, un-see it. As in many of these memorials, it is St. Paul’s Cathedral that is represented.

Ely Cathedral

The cathedral at Ely has had a long-suffering past. The building was completed in 1083 as a Benedictine Abbey and was granted cathedral status in 1109. The building originally had a stone spire of the crossing, predating that of Salisbury Cathedral by some 170 years. Architecture at that time did not quite understand the principals of geometry and load balancing; the spire collapsed into the nave in 1322 (no one was in the building at the time). It was decided that the spire not be rebuilt. It took 18 years, but a magnificent octagonal lantern tower was built in its place. It still confounds architects to this day.

In 1539 the Monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII (just because he wanted an annulment that the Catholic Pope would not grant). Like many other monasteries, Ely suffered destruction and vandalism. The north section of the west front was completely destroyed (and has never been rebuilt). Many statues and windows were also destroyed.

It is some kind of miracle that the building was never burned by Henry’s vandals, nor bombed by the Germans. The original wooden ceiling remains and is painted to represent the lineage of Jesus.

One does not expect to find a “war window” in such a place, but it is there—hiding in a side chapel. It is subtle to a point. It depicts the cathedral (one can clearly see the external architecture of the lantern) and a solitary Spitfire plane flying overhead.

I had a specific reason for going to Ely. The Lady Chapel. Completed in 1349, it is, perhaps, the most acoustically perfect space for music in Great Britain. It is in the Lady Chapel that The Cambridge Singers do most of their recording. (Why not in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge? Who knows.) It is an amazing space, except for the weirdo, arms-to-the-sky, virgin Mary.

One can only imagine its splendour in the days before the Reformation. There are still a few traces of bright paint and coloured glass, but it is still a magnificent room.

Epilogue

There is a church in London that did not get rebuilt. It serves as a memory of the events of the past while serving as a celebration of peace. The columns have been replaced with wooden structures. The sanctuary is now a rose garden with hanging ivy on the pillars.

The war memorials remind us of things past; promising history will not repeat itself.

Support Us

Support Us

Comments ()